Father of Serengeti_Dean James Martins

It was Africa at the dawn of the twentieth century. A raw and virginal

continent; stupendous, and arrogant in its contempt of civilisation.

Africa of the mighty jungle and the vast plain. Of untraversable

deserts and insurmountable mountains. Africa of the pyramids

and of the Savannah. Of towering cliffs and roaring, rushing rivers.

Africa of impenetrable forests and mysterious caves. Of the Congo

and the Kalahari.

Africa of strong proud peoples. The Arab and the African. Africa

of tribespeople – a like, yet so greatly dissimilar. Of resplendent

kingdoms and powerful chiefdoms. Africa of a myriad ethnicities and

a thousand tongues. Of fierce warriors and tall, strong women who

were the wealth and pride of their communities. Africa where

superstition reigned, where witchdoctors who knew the wisdom and

magic of the ancients ruled.

Africa for the wild animal. For the bataleur and the barracuda. Africa

of the hunter and the hunted. Of the lion and the gazelle. Africa –

where every conceivable form of nature flourished, where the

wildebeest could be counted in their millions as the earth shuddered

under the their stampeding hooves. Africa of the trumpeting elephant

and slithering python. Of the cheetah that ran with the speed of wind

and the rhino that bore a horn of majesty. Africa of the crocodile that

lay submerged beneath the waters of murky swamps. Of the vulture

that rode the wind in search of carrion.

Africa of a million varieties of bird that filled the air with shrieks

and birdsong.

Africa of unforgiving climate. Of skies that scorched and showered

the earth at whim. Africa of a sun that baked its subjects and reddened

the horizons with shimmering heat, then drenched the very same

surroundings with impunity, with storms of thunder and lightning that

tore up trees a hundred feet tall.

Africa of a thousand deities and gods. Africa of the ancestors;

uncowed, unforgiving, untamed. Africa that was bound by none.

A continent to be strong in.

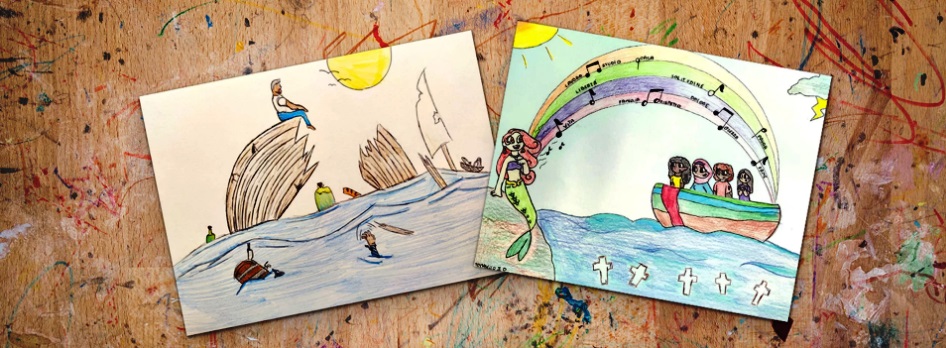

It was to this Africa that Fr. Angelo di Fransisco came. On a ship of

timber and canvas-sail, with a bible and rosary, in a cassock and

collar. He braved the unknown and sailed round the world many

miles from Sicily to Zanzibar, trekked many more with a caravan of

Arab merchants from Zanzibar to Mombasa, and drove the last

hundred by a cart of oxen to the Serengeti plains, home to the Maasai,

a tribe of nomadic pastoralists.

In Maasai folklore, it had been often told that there would be a time

when strange men of pale skin would come to them. Now the

prophecy had been fulfilled. His lined, white skin contrasted sharply

with the rich darkness of the black skin of the Maasai. His straight,

brown hair that ruffled in the winds soaring across the plains with the

force of the mighty Kilimanjaro behind them was unlike the redochre

braids of their men or the clean-shaven heads of their women.

His intense blue eyes marvelled at the splendour of majestic forces of

nature that he saw at play all around him. At the insects that buzzed

with a ferocity that surprised the unwary.

In the Enjeera he was welcomed and befriended. To the Maasai, he

was Nkuba Msungui, the “white chief from across the seas”. To him

they were the children of the God of his faith. It was amongst these

people he settled.

The tribe made him a gift of a mud hut. The hut was low roofed,

thatched and circular. Its round mud walls were plastered with the

dung of the many cattle that belonged to the tribe, that filled the hut

with a pungent odour. His bed was but a hide of a single bull, whose

horns were ornaments that adorned the entrance to his dwelling. A

red-earthen clay pot sat on three large stones in the centre of his hut.

Calabashes sat in a dark, cool corner holding juloti, the mixture of

milk and cow-blood that the Maasai drank each day.

In the ensuing years both the tribespeople and Fr. Angelo learned

much about each other. He embraced their culture and learned of their

beliefs and ways of life. He began to speak their language with ease.

He learned of Enkaai the sky-god of the Maasai and of the cattle that

were the very lifeblood of their existence. He learned of the feared

ancestors and spirits of the skies, earth, rivers, trees and animals.

He took part in their cultural ceremonies. He watched their rites of

circumcision and initiation into adulthood. He often spent days with

them herding their cattle, with the boys in the scrubland who stood

still on one leg for hours on end, silhouetted against the horizon like

statues of sculpted stone. He ate their meat and each day he drank

juloti with the tribespeople.

He learnt of the revered elders, the leaders of the tribal communities.

Often he sat and spoke with them and marvelled at their strength

of character and wisdom. He drank their naisho, traditional beer

from the central pot, from which each man shared by pulling

at a long reed straw.

At the end of his first year with them, the Maasai made him a present

of ten heads of cattle, a bull and nine cows. It was a gift that paid him

the highest compliment for amongst the Maasai nothing is as valuable

as cattle, given to them by Enkaai at the beginning of time. He tended

them well and with time his tiny herd grew and prospered.

In turn, he taught them of his country, from the land whence he came.

He shared the richness of his culture with them and explained a world

so different from their own.

He described the outstanding architecture of the Roman Empire, the

churches and cobbled streets. He told them of the vineyards and of

the wine, the naisho that his land was famous for. He explained the

use of guns and cannons and their superiority to the Maasai spears.

He spoke of the ways of life of his people, of their art and music.

He showed that ties to family amongst his people were as strong as

the Maasai’s own.

To some he even began to teach his tongue. They laughed as they

mouthed the strange sounding words. Amongst them, one girl in

particular was captivated by Fr. Angelo. Her name was Nkolana, she

was the daughter of a respected elder and an outstanding beauty. Her

skin was rich, as brown and smooth as burnished bronze. Her head

was clean-shaven as per the custom. She was tall, well formed, strong

and of good gait. She was graceful, as she walked from the river with

a pot of water balanced carefully on her head she stood out from the

other nditos. She was a hard worker and the cause of much pride in

the community. Many young girls were brought to spend time in her

company, in the hope that they would be influenced by her gentle

nature and quiet character.

Fr. Angelo had noticed her too. She was the most eager of his students

when he taught them of his home. And one of the few Maasai women

that had been unafraid to partake in Christian mass. She often helped

him out with his daily chores, when she had done with her family’s

and the community’s.

In 1914, when Fr. Angelo had lived amongst the Maasai for seven

years, another stranger was to come to the tribe. Irene O’Shaughnessy

was Irish, a nun and a severe woman of forty-five. She had seen much

hardship in life and little joy. Her face was lined and harsh of

expression.

Her life was dedicated to God and she chose to live it in Africa.

As Fr. Angelo, she too was accepted in the community. It was yet

time before white men would be considered the enemy.

It was thought at first that she was Fr. Angelo’s wife, for amongst the

Maasai who count part of their wealth in the numbers of their wives

and sons nothing is so strange as a man who would not marry, now

here was a celibate woman! The elders pondered over this that night

and concluded that the msungui were indeed strange in their habits.

She helped Fr. Angelo in much of his work and he was grateful to her.

Many days thus went by peacefully for the tribe. Fr. Angelo and

Nkolana grew closer. Their attachment to each other ran deep, though

the men of the tribe saw no reason for suspicion, as they knew Fr.

Angelo to be a man of God.

There came a time when Fr. Angelo and Nkolana were alone in the

hut that served as a chapel. It was evening and the orange-gold of the

setting sun lit up the plains and bathed it in a light that seemed to set

the entire earth on fire. The cattle were rounded up in their kraals and

meat was roasting for supper. Nkolana had swept the earthen floor

and now stood and faced Fr. Angelo.

Fr. Angelo looked up from the diary in which he was writing and met

her gaze. In the light of the setting sun, now a deep russet-red, she

seemed to glow, aflame with an opalescent countenance. His heart gave

a start, for the feelings which she now stirred in him were unknown to

him before, for until then he had lived his life for God in celibacy.

Unaware of what led him to her, he stood from the huge tree-trunk

that he used as a table and reached out to her. The tumult that was in

his heart was in hers too, they embraced. Each held on to the other’s

embrace, neither willing for the moment to end. Time and cultural

identity ceased to exist.

At that moment, Sr. Irene stepped into the hut from the small

vegetable garden that she had planted and had been tending.

Transfixed, she stared at the sight before her – such as she had never

seen before. Gathering her habit about her she turned and rushed from

the hut. Fr. Angelo and Nkolana turned as she did, each still entwined

in the arms of the other.

Quietly Fr. Angelo turned to his beloved, for that is what she was, in

truth. With a fear in her heart that could be seen in her eyes she turned

to him and asked “What have we done? What are these feelings we

have?” His heart pained to see the confusion she was in. He traced his

fingers down her cheek gently, and held it in his palm. “Let it be”, he

said, “we have done no wrong”.

He gazed deep into her eyes, brown and soft. “Nkolana”. He spoke

her name, tenderly, quietly, realising for the first time how beautiful it

sounded and how much it meant to him. “Go to your hut, I will sit

here and think of what to do”. Trustingly, she obeyed.

After she had left, he sank to the earthen floor wearily. His mind

raced with a thousand thoughts. What were he to do? That he loved

her he was sure of. For never before had his heart been so full of such

pure an emotion.

After the hour had passed and night had fallen, he arose and walked

across to Irene’s hut. She was quiet, seated on a small log with her

bible in her lap and her rosary between her fingers. Her mouth moved

silently as she prayed, the repetitions soothing her, calming her

troubled mind.

As he tapped her door lightly and entered, she turned and faced him

stoically. Before he could utter a word she said to him “I have written

to the Monsignor Emanuele in Rome”. She said, “we will await his

reply”. With his calm demeanour he met her eyes “Irene, I have done

no wrong, neither has the child”. Irene sat, unmoved. Then she spoke

“that is for our superiors to decide”.

The weeks passed uneventfully. Irene refused to take part in Mass, or

have anything to do with Fr. Angelo or Nkolana. In desperation, Fr.

Angelo turned to the Maasai council of elders for guidance. The

elders heard him out patiently and sat each night around the fire with

their naisho in a quandary, for never before had they been faced with

a dilemma of such proportion. The idea of the proposed marriage of

Nkolana to Fr. Angelo was repulsive to some. They knew that their

decision would set a precedent for the tribe, and their blood would

henceforth be diluted.

“This man means no harm”, said bayan Kimiya, the oldest of the

men, whose wisdom was much respected. “He has lived amongst us

for such a very long time, yet he has respected our customs and even

helped with our ill with powdered medicines from across the seas”.

“Yes, he has certainly helped”, spat bayan Loriso, Nkolana’s father,

his voice tinged with bitterness. “Now I will no longer be of any

standing amongst my own people”.

“You know how it is with matters of the heart”, said yet another,

“nothing ruled by the heart is rational, but to give our daughter in

marriage to Fr. Angelo would be to dishonour her family and weaken

the blood of our descendants”.

Bayan Loriso was the last to speak. “His blood is not weaker than

ours, does he not eat with us, guard our cattle and even hunt with us,

though in his youth he knew nothing of these matters”.

It was amid all this that Fr. Angelo decided to travel to Italy. He knew

that his mind was made up, and indeed the Church would hurry him

along to a conclusion in this matter. He knew that Monsignor

Emanuele would expect it of him. The journey was tedious, for he

knew the controversy that awaited his arrival.

He arrived in Italy as Europe prepared for the first world war. Gunfire

and sirens rent the air every so often. Bombers screamed overhead.

The nations were bent on annihilation and extermination and he

longed far more for the peace of Africa, the stillness of the African

night, the chirruping of the insects, the winds that whistled through

the grass of the plains and Savannah, and the gentle Maasai tribe that

he had grown so attached to.

The horse-drawn carriage that took him at the Cathedral cost him

eight times as much as it had when he had left for Africa. In times of

war, the cabby had grinned with a mouth full of broken teeth.

The passing years had been unkind to the Monsignor, he had aged,

and the signs of his aging were manifest all over his being. His face

was heavily lined, the wrinkles ran deep and his step had weakened

considerably. When he had received Sr. Irene’s letter he had been

deeply disturbed, for Angelo was like a son to him, the Monsignor

had known since his youth and had been his friend and mentor.

Fr. Angelo made his way to the Monsignor’s chambers. The two men

of the cloth faced each other across the room. Each greeted the other

with true warmth, for they had been part of the Church together for a

time that transcended any differences that now stood between them.

“The peace of our Lord be with you” –

– “And also with you”.

It was a greeting that was potent in its simplicity.

“you have come”, said the Monsignor, “I am glad – for we have much

to discuss.” He walked to his desk and took a letter from the first

drawer, handing it to Fr. Angelo he said, “Two months ago I received

this letter from our dear sister Irene, who serves in the same

community that you do on the continent. I shall not ask you to read it,

for I am sure you are well aware of its contents.” Fr. Angelo remained

quiet and standing. The Monsignor Emanuele motioned to the seat

before his desk “Sit,” he said, “sit and tell me of what has come of

your time in Africa.”

Fr. Angelo sat before the Monsignor, and began to speak. His voice

was filled with a passion that welled up from the strength of the

emotions that he was feeling. He spoke of his arrival in Africa and of

his life amongst the Maasai. He told his superior of the Serengeti and

the Maasai, much in the same way that he had long before spoken of

Italy to the tribal elders.

He spoke of the African people that he had grown to cherish as if they

were his own. At the end, he spoke of Nkolana and of the special

place that she held in his heart and being. Monsignor Emanuele

listened patiently, he was an old man and had passed through many

places and learned much in his own life. He knew that there would

come a time when the Church would have to face the predicament of

Fr. Angelo that was before him now.

As Fr. Angelo drew to the end of his tale Monsignor Emanuele

sighed. In the end he knew the decision was not his to make. It was

Fr. Angelo’s. And from what the man had said, he knew too that the

truth was in the heart and the soul of the man who sat before him.

Monsignor Emanuele waved his spotted and gnarled hand. “My son,

your decision is in your heart. When you joined this Church years

ago, you were asked to take, but three vows; poverty, chastity and

servitude. Perhaps in Africa, with Nkolana and amongst your Maasai

friends, by embracing their ways of life you have truly lived out those

vows to a greater extent than those of us that live here, enemies with

our neighbours, hoarding our wealth, and living in times of war.”

“Should you choose to leave us for Nkolana, you have my blessing. I

will make the necessary arrangements for your step-down from the

Church. Go in peace, return to Africa, live as one of God’s own.” Fr.

Angelo took the aged hand in his own, kissed the ring on its third

finger, then kissed both the cheeks of his mentor. “Thank you,

Monsignor.” It was all he could say.

Fr. Angelo left the Monsignor’s chambers and walked to a chapel.

There he knelt before the crucifix of his Lord and Saviour and prayed

from the depth of his spirit. The hours passed, but in his communion

with his Creator he was unaware of time. He prayed that he would be

forgiven his decision, that he would be true to Nkolana and blessed in

his future with her people.

He prayed for the understanding of the Church superiors and the

Maasai elders. He prayed till the sweat poured from his brow. In the

dead of the night, exhausted, he rose from his knees.

That night he slept with a light heart.

He lived in Italy but for a few weeks. He found it strange to call this

“home” when the home of his spirit was now so different and starkly

dissimilar a thousand miles away in Africa. He arranged his passage

back to Africa with haste. He visited family and friends, bidding

farewell as he had once done decades previously. On his last day

home he visited his parents graves, laying wreaths on each stone slab,

bidding them a final farewell.

As he boarded the ship, he kissed the earth of the shores of his

motherland. In his mind he spoke to the land “farewell, you beautiful

country”. He made the journey fevereshly, the weeks rushed by. For

he was returning to love and life, to hope and dreams. Sea, caravan,

oxen-carts, then at last he was in the arms of his beloved, on the

plains of steppe that danced all day and night.

The elders had agreed to a marriage between him and Nkolana. In

honour of their custom of bridal-price, Angelo gave the entire herd he

owned to bayan Loriso.

The tribe prepared for the their wedding as they did for all weddings,

with laughter and merriment and feasting and much rejoicing.

When the matters of matrimony had been finalised, Nkolana left her

mother’s hut for her new husband’s. A larger hut had been prepared

for them, in the centre of the manyatta, where they would be one with

all the tribe’s members. The night that she moved there was a feast.

The aroma of roasting meat filled the air, as the people basked in the

heat of the fires. Tendrils of pungent wood-smoke drafted upwards to

meet the dark sky, with stars as large and bright as diamonds.

Angelo and Nkolana sat together. Close in heart and mind and spirit.

Happiness permeated their entire beings and brimmed forth in their

eyes and smiles. Nkolana had known such happiness would be hers

with Angelo by her side, and against all odds they had triumphed.

That night, when the feasting and rejoicing had ended, they lay

together in their home as man and wife. When their passion was

spent, they spoke in whispers of their future, one to be shared in total

communion. They spoke of the place they would now hold in the

community that they both respected. They spoke of children they

would bring forth together – strong sons and fine daughters. They

spoke of cattle and the herds that they would raise.

The months passed, and Nkolana grew heavy with child. Angelo

watched over her tenderly as did Nkolana’s own mother. When the

time for the birth grew near Nkolana returned to her mother’s hut.

Each day Angelo visited her, regaling her with tales of humour and

telling her of how much their child meant to him.

On a cold, clear morning when the first faint pink of light touched the

eastern horizon of the savannah, Nkolana began her labour. The pains

wracked across her swollen womb as the child inside her felt the

insistent pushing that would bring her to the world. Her mother and

other women of the tribe came to Nkolana and watched her carefully,

waiting for their child.

Hours later, Nkolana called to her mother. She felt that the time had

come, the child inside her would be patient no longer. She groaned

deeply and gulped in huge breaths of air. Her mother and aunt bent

above her as she used the might of her strong frame to push her little

child into their waiting hands. Nkolana heaved, and the wail of the

newborn filled the tiny hut.

Ululations from the womenfolk rent the air. The news was passed

from hut to hut. A girl – a girl has been born to Nkolana. The tribe

thanked the ancestors.

Sr. Irene had come to them, with a gift of a shawl for the child. As

she looked at the scene before her, her heart melted, the hardness

softened and she was once again a friend.

Later that night, Angelo watched as their tiny girl suckled. Nkolana

looked into the eyes of her husband, weary but proud. He lifted his

sleeping daughter to his cheek, and touched the soft silk of her skin.

He carried her gently, crooning to her as one can only croon to a

newborn child. Then he lay beside his wife and the family slept.

The following morning they named their daughter – Serengeti – for

the land in which they had loved and lived. The land that had taught

them strength.